HOME

Museum &

Collections

Sales

Donations

Events

Contact Us

REGIMENTAL HISTORY

17th Century

18th Century

19th Century

20th Century

First World War

Second World War

Actions & Movements

Battle Honours

FAMILY HISTORY

Resources

Further Reading

PHOTO GALLERY

ENQUIRIES

FURTHER READING

LINKS

© Images are copyright, Trustees of the King's Own Royal Regiment Museum.

You must seek permission prior to

publication of any of our images.

|

|

Museum Display Information

A Soldier’s Life 1870-1900

The final decades of the 19th Century were a period of change and

reform in British society and this was reflected in the army. Recruits

came from towns rather than the countryside. Soldiers saw improvements

in their living conditions and pay as a result of reforms. Through the

period the army offered stable employment, and a good life.

Recruiting

The Cardwell Reforms revised the terms of service for ordinary

soldiers to encourage young men to join the army. Recruits now enlisted

for twelve years - the first six with the Colours (Regular Army), the

remainder in the Reserve. This was later altered to seven years and

five.

If army recruiting was going particularly well more men could be

encouraged to move to the Reserve. Thus the average age of soldiers was

lowered and the number of old soldiers, often addicted to rough

behaviour, heavy drinking and hard swearing, was reduced.

Soldiers were now able to ‘purchase’ their discharge - so it was

possible for them to leave the army. The cost was more than their annual

pay - £18.

The army could be seen as one way of escaping poverty at home. Of a

total of 178,064 men in the army, in the last quarter of the 19th

Century, almost 25% came from depressed rural areas and city slums.

Rural poverty in Ireland may account for the fact that 39,121 of the

soldiers were Irish.

From the 1870s fewer recruits were coming from the countryside. The

industrialisation of Britain had shifted the population to urban areas

and the majority of recruits were leaving city slums, rather than

depressed rural areas.

In 1870 the Elementary Education Act brought some level of compulsory

education to all children. More and more recruits were literate and

harder to deceive than the county recruits of twenty years before.

The appeal of the army:

| pay was regular |

| food was ample |

| employment was secure |

| the uniform was glamorous |

| there was promise of adventure |

| barrack accommodation was improving |

Pay

The army offered secure employment and regular pay.

Soldiers were paid four times a month, on the 1st, 8th, 15th, and 22nd

of each month. On each pay day there was a notable increase in the

number of men who were drunk and rowdy. This was not uncommon amongst

civilian contemporaries.

The pay of the Private soldier was increased to one shilling a day in

the 1880s. However, a number of deductions for such things as groceries,

tea, and washing clothes were made. Meat and bread were free. Other

improvements in living conditions were made. Higher ranks were far

better off.

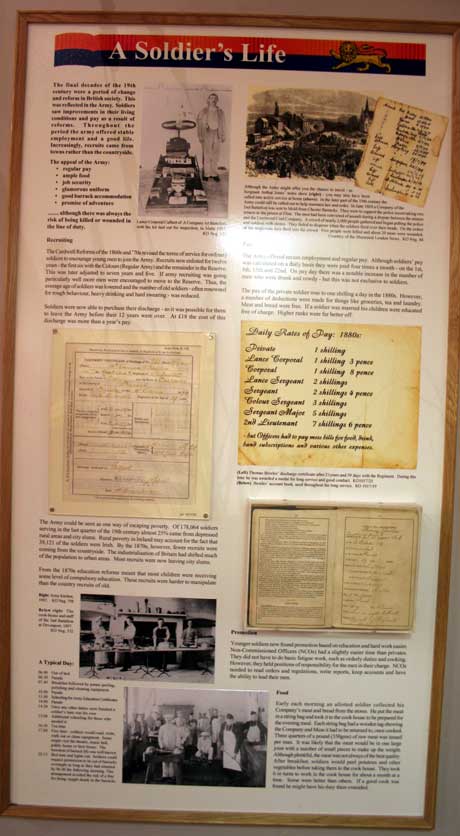

Daily Rates of Pay: 1880s:

| Private 1 shilling |

| Lance Corporal 1 shilling 3 pence |

| Corporal 1 shilling 8 pence |

| Lance Sergeant 2 shillings |

| Sergeant 2 shillings 4 pence |

| Colour Sergeant 3 shillings |

| Sergeant Major 5 shillings |

| 2nd Lieutenant 7 shillings 6 pence - but had to pay mess bills

for food and drink, band subscriptions, plus various other expenses. |

If a soldier was married his children were educated free.

Promotion

Younger soldiers now found promotion easier, based upon education and

hard work. Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) had a slightly easier time

than Privates. NCOs did not have to do basic fatigue work, such as

orderly duties and cooking, however they held positions of

responsibility over the men in their charge. NCOs needed to read orders

and regulations, write reports, keep accounts and have the ability to

lead their men.

Food

Early each morning meat and bread for the Company would be collected

from the stores. The meat was placed in a string bag and taken to the

cook house. Each string bag had a wooden tag to identify the Company and

Mess to which it had to be returned, once cooked. Meat was issued at

three quarters of a pound per man (uncooked) and it was likely that the

meat would be in one large joint and a number of small pieces to make

the weight. Meat was not always of the best quality. After breakfast the

men would peel potatoes and other vegetables which were also taken to

the cook house.

Soldiers would take it in turns to work in the cook house, usually about

one month at a time. Some were better than others and if a good cook was

found he would have his time there extended.

A Typical Day:

| 06.00 Out of bed |

| 06.30 - 07.30 Parade |

| 07.45 Breakfast followed by potato peeling, polishing and

cleaning equipment. |

| 10.00 Parade |

| 11.00 Schooling for Army Education Certificates |

| 14.00 Parade |

| 14.30 Once any other duties were finished, your time was your

own |

| 15.00 Additional schooling for those who needed it |

| 16.30 Tea time |

| 17.00 Your time was your own. |

| Soldiers would read, write, walk out, or clean equipment, Some

might visit the theatre, music hall, public house, beer house but

boredom of barrack life was well known. |

| 22.15 Bed time and lights out. |

Soldiers could request permission to be out of barracks overnight, as

long as they had returned by 06.00 the following morning. This avoided

the risk of being fined for being drunk in the barracks.

© Images are copyright, Trustees of the King's Own Royal Regiment Museum.

You must seek permission prior to

publication of any of our images.

Only a proportion of our collections

are on display at anyone time. Certain items are on loan for display

in other institutions. An appointment is required to consult any of

our collections which are held in store. |