Museum Display Information

Soldiers Life 1700s

A Soldier’s Life was totally different in the 1700s to what any

soldier would expect in today’s modern army. Regiments had no permanent

base. Soldiers spent the summer in tented camps, and in winter billeted

in inns or private houses. Army life was not easy - but all the soldiers

were volunteers - and not ‘pressed’ as in the Navy. The Army offered

regular food, pay and usually a roof overhead - things which were not

guaranteed in civilian life.

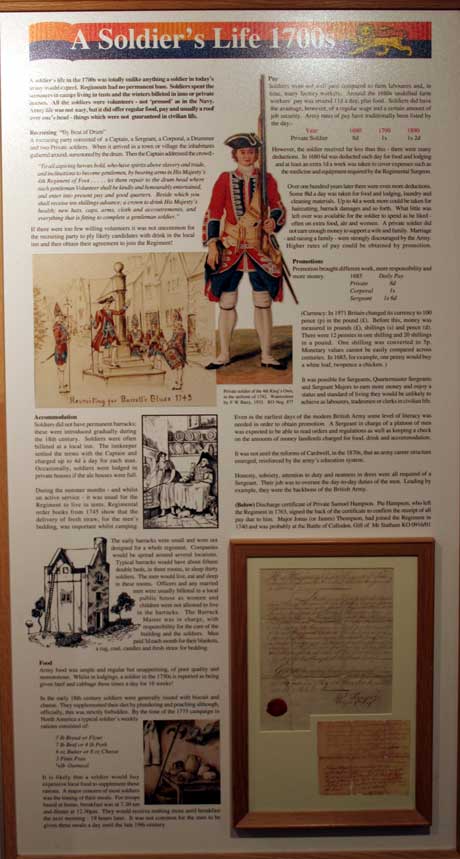

Recruiting "By Beat of Drum"

A recruiting party would consist of a Captain, a Sergeant, a

Corporal, a Drummer and two Private soldiers. On arrival in a town or

village the inhabitants would be summoned by beating the drum.

The Captain would address the crowd:-

"To all aspiring heroes bold, who have spirits above slavery and trade,

and inclinations to become gentlemen, by bearing arms in His Majesty's

4th Regiment of Foot . . . . . let them repair to the drum head where

each gentleman Volunteer shall be kindly and honourably entertained, and

enter into present pay and good quarters. Beside which you shall receive

ten shillings advance; a crown to drink His Majesty's health; new hats,

caps, arms, cloth and accoutrements, and everything that is fitting to

complete a gentleman soldier."

If sufficient volunteers were not forthcoming it was not uncommon for

the recruiting party to ply likely candidates with drink in the local

inn, and then obtain their agreement to joining the Regiment!

Recruiting for Barrell's Blues

Accession Number: KO2490/304

Accommodation

Early soldiers did not have any permanent barracks; these were

introduced gradually during the 18th century.

Soldiers would often be billeted with a local innkeeper, who would agree

terms with the Captain. He could charge up to 4d per day per man.

Occasionally soldiers could be lodged in private houses if the ale

houses were full.

During the summer months and while on active service, it was usual for

the regiment to live in tents. Regimental order books from 1745 show the

delivery of fresh clean straw, for bedding, was important while men were

camping.

The early barracks were small and not designed for a whole regiment.

Different companies would be spread over a few locations.

A typical barracks would have about fifteen double beds in three rooms,

which would sleep thirty soldiers. The men would live, eat and sleep in

these rooms. Officers and any married men were usually billeted in a

local public house as no women or children were allowed to live in the

barracks.

The Barrack Master was in charge and was responsible for the care of the

building and the soldiers. Men paid 3d each month for blankets, a rug,

coal, candles and fresh straw for bedding.

Pay

Soldiers were not well paid compared to farm labourers and factory

workers, but they did have a regular wage and a certain amount of job

security.

Army Pay Rates have traditionally been listed as by the day:-

In 1680 a private soldier was paid 8d (pence) per day.

In 1790 a private soldier was paid 1s (shilling) per day.

In 1890 a private soldier was paid 1s 2d per day.

The pay the soldier actually received was far less - there were many

deductions. In 1680 6d was taken each day for food and lodgings, and at

least an additional 1d was taken each week to cover various expenses

such as the medicine and equipment required by the Regimental Surgeon.

Over one hundred years later the deductions had increased. 8¾d per day

was taken for food and lodging, laundry and cleaning materials. Up to 4d

per week would also be taken for various things such as barrack damages

and haircutting. What was left over was probably spent by the soldier on

additional food, ale and prostitutes.

A private soldier did not earn enough money to support a wife and

family; families were strongly discouraged by the Army.

Higher pay could be obtained by promotion.

Promotions

Promotion brought different work, more responsibility and more money.

1685 Daily Pay

Private 8d

Corporal 1s

Sergeant 1s 6d

(Currency Explanation: Before 1971 money was measured in pounds,

shillings and pence. There were 12 pence in one shilling, and 20

shillings in a pound. One shilling was equal to five pence as we know it

today.)

It was possible for Sergeants, Quartermaster Sergeants and Sergeant

Majors to earn more money and enjoy a standard of living and status

which they were unlikely to achieve as labourers, tradesmen or clerks in

civilian life.

Even from the earliest days of the modern British Army some level of

literacy was expected in order to obtain promotion. A Sergeant in charge

of a platoon of men would be expected to be able to read orders and

regulations, and check the amounts being charged by landlords for straw,

candles, food and drink and accommodation.

It was not until the reforms of Cardwell in the 1870s that an army

career structure began, reinforced with a proper system of Army

Education.

Sergeants needed honesty, sobriety, an attention to duty and a neatness

in dress. Leading by example they were the backbone of the British Army

- overseeing the day- to-day duties of the men.

Food

Army food was unappetizing of poor quality, monotonous, but was ample

and regular.

Whilst in lodgings a soldier in the 1750's is reported to have been fed

beef and cabbage three times a day for sixteen weeks!

In the early 18th century soldiers were generally issued with biscuit

and cheese. They would supplement their diet by plundering and poaching,

although this was strictly forbidden.

By the time of the 1775 campaign in North America a typical soldier's

weekly rations consisted of:

7 lb Bread or Flour

7 lb Beef or 4 lb Pork

6 oz Butter or 8 oz Cheese

3 Pints Peas

½ lb Oatmeal

It is likely that a soldier would supplement these rations by buying

expensive local food.

A major concern of most soldiers was the timing of their meals. For

troops based at home breakfast was at 7.30 am and dinner at 12.30pm.

They would receive nothing more until breakfast the next morning - 19

hours later. Three meals a day did not become common until the late 19th

century.

Accession Number: KO2217/05

© Images are copyright, Trustees of the King's Own Royal Regiment Museum.

You must seek permission prior to

publication of any of our images.

Only a proportion of our collections

are on display at anyone time. Certain items are on loan for display

in other institutions. An appointment is required to consult any of

our collections which are held in store.