Soldiers of the Regiment

Mrs Elizabeth Evans

Mrs Evans, wife of Private William Evans, was one of only three wives

of the regiment in the Crimea and is the only women to have received a

regimental funeral.

Mrs Elizabeth Evans with Chelsea Pensioners of the King's Own Royal

Regiment, including veterans of the Crimea, Indian Mutiny and Abyssinian

and Zulu Campaigns, circa 1912. She married into the Regiment in

1852 and accompanied her husband to the Crimea, one of only 17 women to

do so. Of the 17, only three, Mrs Evans, Mrs Rebecca Box and Mrs

Chilton went to the front. Mrs Evans remained with her husband

until she fell ill with fever in late 1854 and was evacuated.

After her husband's death she was given permission to wear his medals.

She died on 30th January 1914 and was buried with full military honours,

the only woman in the Regiment's history to be so honoured. Back

row: Private W Mahoney, Private W Manderville (who died on 31st May

1912), Private E Evans (no relation), Private W Gosling and

Private A A Knight. Front row: Private D Hearsum, (seated) (who

died on 2nd February 1913; Mrs Evans and Private A Smith (seated).

Accession Number: KO1783/06

From the Lion and Rose of April 1909

A Soldier’s Wife in the Crimea

From the Narrative of Mrs Elizabeth Evans, late 4th King’s Own Regiment

of Foot. As told to Walter Wood. [From the “Royal Magazine”]

As a vivid picture of the long and terrible sufferings of our womenfolk

during the Crimean War, no story that has been published exceeds in

interest this narrative of a gallant lady, who accompanied her husband

to the seat of war. Mrs Elizabeth Evans was married in 1851, and joined

her husband’s regiment, with which she proceeded to the Crimea. After

serving in the Army for twenty-one years he retired, and died just

before his golden wedding was to have been celebrated. Mrs Evans has a

small pension, and enjoys the distinction of wearing her husband’s

medals. She is still in excellent health, and full of that wonderful

courage which enabled her to survive the notorious hardship of a

woefully mis-managed campaign.

You wish me to tell you something about the days when women went to the

wars with their husbands, took part in their sufferings on the march and

on the battlefield, and sometimes shared the last resting place with

them. I will do so.

When I take my mind back to those distant years of suffering by young

women in the Army, I marvel at the changes which time has wrought.

Sometimes I listen to the wails of soldiers and their wives and

sweethearts nowadays, and I smile almost pityingly, for, compared with

the old order, they are ladies and gentlemen, and do not know privation

and iron discipline are. What would some of your Army women to today

think of doing a soldier’s washing for a halfpenny a day, and sometimes

fight to get the work even at that price, because the extra pay meant so

many more little luxuries for the soldier and his wife?

When I married, and that was in 1851, I joined the King’s Own, which was

then at Ashton-under-Lyne in Lancashire.

My new home was a corner of the barrack room in which twenty four men

lived and slept. I and my husband ate and drank and slept there, too,

our bedroom at night being a corner of the room curtained off. In the

daytime the curtain was removed. Such a thing as that privacy which is

given nowadays to soldiers’ wives was not known then; yet in spite of

these crude surroundings, although the men of the Crimean days could not

for the most part either read or write, they behaved to me like

gentlemen. I want you to remember that, and I wish it to be borne in

mind, too, by some of those foolishly talkative people who have said so

much against the manners and the morals of the men who, whatever faults

they had, were good and faithful friends to me and to the women who

shared my sufferings in the Crimea and afterwards in India.

They were stern and bitter days, yet not without plenty of happiness. I

had my husband, you see, and we were devoted to each other. That makes a

lot of difference in your hard march through life, does it not? He

worked for me, and I for him; and so I was glad enough when I could get

a big share of the men’s washing, at the halfpenny a day each man. We,

the women, washed twice a week for them, and at times, when I was lucky,

I had nearly a score of soldiers on my books. That meant quite a

comfortable addition to the scanty pay they gave the bygone British

soldier. He, poor fellow, was ill fed and under fed, and anything he

needed or craved for in the way of luxuries he had to buy out of his own

pocket. It was wonderful to see how great a value he set on a halfpenny.

Every night, when the orderly officer had been his rounds, the pole was

put up and the curtain drawn, and there, in the corner of the big

barrack room, I slept. If ever there was anything which might have been

objectionable on the part of any of the men it was soon stopped, I can

tell you; but, truth to say, I seldom had any cause to complain.

I often think of the first dinner I saw put on the table in that barrack

room. A large bowl of soup was brought out; and beef in one net and

potatoes in another. That was the dinner, but the things which troubled

my mind was the absence of a table cloth! How speedily was I to learn

what a trifle the absence of linen and such luxuries was! I was to see

the day come when there were as many as four married women in a single

barrack room, living with the men, and sometimes dying amongst them;

and, not seldom, giving birth to children. Think of that, you young

ladies and gentlemen of the Army nowadays, some of you who expect your

husband to have a servant of his own and your own child to have a nurse

– and I am not now speaking of the officers, mind you, but the

non-commissioned ranks. It may have been selfish of me, but I was

happier when I was the only women in the barrack room than I was when I

had to share it with other members of my sex.

Happy days must have an ending – ah! how swift the finish sometimes

comes – and the shadow of war in the Near East was oppressing England.

Troops were being sent away from all our ports, it seemed, bound for

that dreadful country which will always be associated with suffering.

My own regiment – you see, I cannot help speaking of the brave old 4th

as mine – was under orders, and to the Crimea we sailed, starting from

Leith, in a ship they called the Golden Fleece.

We got to Malta, and then we went ahead and reached Gallipoli, where so

many of the fighting people landed. There were just three women with the

regiment when we landed. A few had been left in Malta, and the officers’

ladies had gone elsewhere.

The three women made a remarkable mixture, for they represented the

United Kingdom. I was English, there was an Irishwoman, and there was a

Scotchwoman. We were together at the beginning, and much of suffering

and excitement we saw; but the time soon came when we parted, and during

the whole of the two years that I spent in the Crimea I never saw

another woman. We lost sight of each other; they were taken from me –

and, indeed, in that ruthless land it seemed as if everything on which

my heart was set was likely to be torn away.

Talk of impressions and memories! The first and clearest of them all are

those of locusts and cholera – locusts so dense and innumerable as to

look like black clouds. Were the symbolic of the shadow which came

across the lives of so many of us? Were they the forerunners of that

dreadful visitation which struck strong men down even as they worked and

marched, and made their halting places their graves? Many a fine soldier

I saw in health and strength, and a few hours later I marched away with

my regiment, leaving him at rest. Terrible, indeed, the sickness was;

but it was at least merciful, and most of us who have been through

life’s great sorrows, and have seen the sufferings of those we love,

know that for such brevity of illness we have cause to be thankful

evermore.

Many and pitiful were the scenes I witnessed in those early days before

the actual fighting began, none more sorrowful than the case of a poor

young thing who was a sergeant’s wife. She was stricken with the

cholera, and the heartbroken husband rigged up a sort of little tent to

cover her. They sent for me, and I joined her just as the sun was

setting. I wanted a light, as darkness comes so swiftly there, and I

told the sergeant to go and fetch a candle. Then I turned to the young

wife.

“Look at the beautiful sun, dear,” I whispered.

“Ah, me!” she answered. “I shall never watch it rise again. Turn me

round so that I can see it for the last time!”

A drummer boy was standing near, and, as the sergeant had not come back,

I told him to run and fetch a candle. He hurried off, and I tried to

turn my poor darling to the golden light, which so wonderfully flooded

the skies in the west, towards home and England.

She looked – and she died, and within an hour or so the Engineers had

buried her, and everything belonging to her had been burnt. Many such

sorry cases there were; but that I remember best of all, because, you

see, it was the first, and she was a woman.

Ah! That terrible, pitiless cholera! Worse, surely, than battle itself –

for, on the field, you did at any rate get the thrill and excitement of

action, and knew that you were fighting and suffering for your country;

but with disease, it is so different, is it not? You can only watch and

wait dumbly, knowing that your enemy is invincible. There was a hospital

at Gallipoli, and one of our men and a woman, husband and wife, were

sent down there as caretakers. They were both victims, and both died

crying out for each other. Yes, indeed, the cholera seemed to sweep

through our ranks, as mercilessly as locusts strip the land of its

verdure.

I landed in the Crimea, in the summer time, and lovely weather it was,

too – just as beautiful as the winter was cruel. With balmy air and

sunshine you can endure many shortages of food and drink and clothing;

but it is different when the icy winds are blowing, when the snow is

falling heavily, and when there is nothing at night between your resting

place and the bitter sky.

When the summer was still with us my husband and I made shift to sleep

in a sort of dug out in the ground, with twigs and branches as

bedclothes; but when the cold weather came the covering was taken away

for firewood. You remember those dark and sorry days, when there were so

many clothes and comforts sent from home for the soldiers in the Crimea?

– necessities which never reached us, but which remained and rotted on

the shores where they had been landed. There were many sad blunderings,

and the result was that many soldiers perished, although the means of

salvation was so close at hand. I used to see the young recruits, fresh

from home, droop and die of starvation and disease; yet with all the

privation and suffering there was such courage and patience shown as

almost put into the shade, I think, the valour of the battlefield.

Did I not go into action, you ask? Was I not a witness of some of the

desperately contested struggles of the Crimea? Yes, indeed, but I still

think that the worst of the war was not the struggle on the battlefield

itself, but the long drawn privations of the trenches, the marches, the

pitiless camps, and the dreadful hospitals.

I had marched and suffered with my husband. It was tramp, tramp, tramp,

for woman as well as man, and I held up to it with a stout heart. I was

young and strong, and I loved my husband. My place was with him, at his

side when that was possible, and always with my regiment.

The order came that we were to go to Varna, because the war was getting

pretty close to us. It was terrible news, for it meant so much. So far

we had been together, I and my husband; now came that most pitiful of

all things – a parting which might so easily by for ever.

My officer sent for my husband. “We are going to embark tomorrow

morning,” he said, “and we are going to meet the Russians. We may get

blown off the face of the earth.”

That was bad enough, but not so bad as when he turned to the three wives

and added: “You women will have to stay behind.”

Stay behind, and our husbands marching off to war! It was more than

flesh and blood could endure – certainly more than devoted wives could

bear. Orders are orders, and discipline is discipline, but women are

women, and glory in circumventing orders, especially when love is

concerned. A loving women must have her way, and the three of us came

under that heading.

We stole stealthily to the beach to see the men embark; but we were

cruelly disappointed. We were forbidden to go near the troops. Think

what it meant to us to be so near and yet so far away.

What were we to do? How were we to get on board? I think it was the

lively little Irishwoman who solved the problem first. There was the

embarkation major flying about, very busy in attending to his hard

duties.

The little Irishwoman looked up and attracted his attention. The major

saw only three forlorn women, and he had compassion on them. They did

not tell him that they had been ordered to remain behind with the sick.

“Be down here early in the morning,” he said, “and you shall go on board

with the first troops that embark.”

How long that night seemed! How little we slept! How fearful we were

that in spite of all our plotting and craft we should be discovered and

ignominiously defeated! There were some English men-o-war’s men on the

beach, making fascines, and – bless their dear hearts! – they gave us

some chocolate and biscuits, and entered into league with us. They tried

to make a shelter for us with two or three sacks; and we trembled ever

moment with the terror of discovery by some one who knew more about us

than the major did.

Suddenly, in the night, we became dumb with fear. We heard the voice of

our quarter master, a dear little gentleman, demanding to know who was

in the sack shelter; but we had described him to the sailors, and they

helped us through to the end.

When the morning came the embarkation officer appeared and said: “Oh!

you three women, come on!” And joyfully, though tremblingly, we

accompanied him. He went to the officer commanding one of the transports

and said: “These three women are to go to the front,” and you may be

sure that we didn’t say anything different.

We were on board, but in three different ships as it proved; and then,

in spite of all, I was ordered to remain on board, while the troops went

to the front!

My husband was almost frantic. But he was not the man to be beaten. The

Commander in Chief, Lord Raglan, was near, and my husband went straight

up to his lordship and said that the other two women had been allowed to

land, and begged that I also might go ashore and accompany the troops.

“I would rather put a stone round her neck and drown her.” he declared,

“than leave her here at the mercy of foreigners.” And I think it was

that which made the Commander in Chief have pity; at any rate, he gave

orders that I was to go ashore, and ashore I went, and from that time I

date my marching in the Crimea. I was to learn what it meant to tramp

for a long weary day, without a drop of water to drink, and so utterly

exhausted that I could have fallen by the roadside, never to rise again.

The Alma was our destination, and terrible as the march towards the

river and the little down was, it was made infinitely worse by the fact

that my husband fell sick, and I lost sight of him. But he came up at

last, not with my own regiment, but with the Guards. I could not keep up

with the column, for my feet were sore and blistered, and my limbs were

weary. My husband, bad though he was, would give me a lift.

“Come on, Lil,” he would say, “you must keep on marching. If you fall

out the Russians will have you, and God knows what will happen then.”

The officers and the men, too, would help and cheer me, and the dear

colonel himself put heart of grace into me.

“Come,” he said cheerily, “keep it up, and if we get back to England I

will see that you have some good clothes.”

I know that if he had lived, if he had come home, he would have kept his

word, but he was killed on the 18th June, at the unsuccessful storming

of the Redan.

The Alma at last! The first real meeting with those Russians of whom we

had heard so much and seen so little; the actual battle field, at the

end, almost, of the glorious summer, for it was now towards the close of

September.

Here is a little steel engraving of the country where the battle was

fought. This is the very spot where I stood, a lonely woman, with the

staff, and saw my husband march away with his regiment to storm those

dreadful heights which frowned with the Russian guns and bristled with

the bayonets.

There were 57,000 English, French, and Turks, against nearly 50,000

Russians, fortified on the heights of Alma, and with 180 field pieces to

protect them. It was terrible to see the position which had to be

stormed; and more awful to watch the men of our army advance to the

assault.

I had suffered many agonies in the Crimea, but none so poignant as that

pain which endured when I watched my husband march across the far

stretched field, which was being ploughed by the merciless cannon-balls

and pitted with the rifle bullets.

So many men marched on, with the Colours flying bravely; so few seem to

get towards the heights which were breaking into tongues of fatal fire,

and strewing the plains with dead and dying. It seemed as if the battle

were some hideous nightmare; yet the dream was so long. Is it not

wonderful that we poor human beings can endure so much and still

survive?

The fight was finished at last, and we, the allies, were conquerors. My

husband, too, was spared, and in the gladness of his salvation I fear

that I almost lost sight of the sufferings and sorrows of the rest. The

Alma was the first and last battle that I witnessed in the Crimea; but

it was more than enough. I do not dwell on its horrors; I try and keep

them from my mind, but I do not succeed, and even now, when I am telling

you about it, I see, just as clearly as I beheld it then, a brave

officer lying where he had fallen, looking with wild eyes towards the

heights of Alma. They were big, merry blue eyes, the most beautiful, I

think, that I ever saw.

The regimental Colours were badly torn by shot at the Alma and after the

battle I was set to work to repair them, which I did as best I could

with my needle. I wonder if there is any other Englishwoman living who

can say that she had repaired Colours which she has seen carried into

action and waving in the battle smoke? Those tattered folds of silk are

now at rest in peaceful church.

The suffering of the sick and wounded was terrible. Poor creatures! I

cannot say that I nursed them – there were no hospital appliances then,

and all I could do was to give them the help of a women’s sympathy. Just

a rough covering or tent was put up, when there was material, and

beneath it our brave fellows were packed like herrings in barrels, and

the three doctors who were with us did all they could. Little enough it

was.

The dreadful winter came, and I was perished with cold and hunger. I had

nothing except what I stood upright in. We had no blankets, but I had a

beautiful great Scotch plaid shawl. This kept me warm to some extent,

and often enough I shared my husband’s greatcoat, and sometimes had it

for myself when he was in the trenches. He would come back from the

awful work shivering and almost frozen, and time after time I would

remove his boots and rub his feet, which were utterly numb, and likely

to come off from frost bite.

Time after time, when it did not seem humanly possible for him to work

in the trenches, I would implore him to go sick, so that he could pull

himself together, but he never would. He never shirked his duty – and I

am proud of it. I was thankful if I could get him a little drop of warm,

weak coffee from the poor old Band Sergeant. How I suffered physically!

But that was nothing to the anguish I endured whenever my husband was

away in the trenches, for fear he would be brought back dying, as he

helped to bring so many, or never return to me.

Being a woman, I was something of a favourite with all ranks, officers

and men alike, and being a wife I wanted to be where my husband was.

That happened to me, at one time, on outlying picket, that is to say, as

near the Russians as it was possible to get. There was nothing but a

little stretch of ground between their nearest sentries and our own, and

often in the blackness of the winter night the sentinels would fire upon

and kill each other. Outlying picket was no place for a woman, but I was

allowed to go because by husband liked to be with me, and I wanted to be

with him. Time after time I went, and I got many a terrible scare.

One day we were out and the Russians got a sight of us. “Now, Mrs

Evans,” said one of my officers, “you had better make your way back to

the camp, because the Russians have got the range of us.” So they had,

and although I faced it out as well as I could I was thankful to turn

and hurry away to a place of safety.

I got quite used to dodging the shot and shell from the Russian

batteries. At night we were guided by the trail of the missiles’ fire,

and in the daytime we were directed by the hiss. Then it was a case of

falling to the ground to wait for the crash of the explosion above your

head, or the appalling burial of the shot or shell in the earth near

you.

We got to take those things very lightly, and the officers would joke

and say: “Let us eat and drink what we’ve got and make the best of it,

for tomorrow our heads may be off our shoulders.” Andoften enough they

were, too. Very frequently, when we were besieging Sebastopol, I would

watch the firing with some of the drummer boys, and it was wonderful to

look down into that marvellous fortress and see the big guns bursting

into lurid fire and hear their solemn booming in the gloomy hills.

When we were marching to Sebastopol I saw a poor Russian soldier

sitting, as it seemed, by the roadside. He was bending down, looking

just as if he were taking his boots and stockings off to dress his

wounds. I went up, meaning to speak to him, and saw that he had been

dreadfully hurt in battle. He did not move, and then I found he had been

killed by his own people to prevent him from falling into our hands. You

see, they thought we treated their wounded as they treated ours. He wore

a leaden charm round his neck, like all Russian soldiers – a simple

cross with Christ upon it. It was secured round his neck with a bit of

string, and I took it off and kept it as a keepsake. I have the charm

still, gilded and fastened to a chain – one of my little mementoes of

the war, and here it is for you to see. It is one of the things that I

could keep – one of the small remembrances that could not be taken from

me, because it was of no use to anybody. So much I could not say of a

chicken that I got in the Alma village – a dear little tame creature

which I had for some time, and of which I was very fond. But it

disappeared, and I knew afterwards that some of the men of the 44th had

turned it into food. I had a kitten too, a brave little chap that used

to stand on my shoulder and watch the screaming shot and shell. He was a

dear pet of mine, but I lost him, and had to march away without him.

The fine weather and the bad weather came and went; the months rolled

by, every day telling its sorry tale of suffering and death. I lived

such a life as few women in existence can speak about –short of food,

without a bed, scarcely knowing what decent clothing meant, and

witnessing heart breaking spectacles of suffering in hospital and

elsewhere. Miss Nightingale had not in those early days gone out to the

Crimea, and I never saw her, for she was at Scutari, and I did not visit

that place.

Strong though I was, I fell a victim to fever. I lay on the bare ground,

where they had put me, and they simply waited for the end, for it seemed

as if nothing could be done for me. There were no nurses, no comforts,

and the best they could do in the way of a pillow was a stone which they

placed under my head. It is not long since a veteran, who lives not far

away, told me how well he remembers putting the pillow for me, but I do

not recollect it. I do, however, know that I suddenly seemed to be

getting better, and that I saw some men coming up with three fresh

planks.

One overwhelming thought oppressed me – due, I know, to those sad things

which I had known so well in the Crimea, and I cried feebly: “Oh, don’t

bury me yet! I’m not dead!” Then they laughed and said “Never mind that

we’ve brought a bed for you.” And so they had, dear fellows. They lifted

me from the ground and put me on the boards. It happened to be lovely

weather, and the first time I looked towards the warm and glorious sun I

thought that I was in a new and better world indeed.

Never can I forget those dreadful parally unconscious hours when the

horror of death oppressed me. I used to cream at a shadow when people

passed, fearing that they had come to bury me. I had no husband to look

after and protect me. He had been sent to Scutari with Russian

prisoners, and I had been left behind because I was too ill to move. Can

you not imagine what the parting meant for both of us? Until I came back

to England I did not know whether he was dead or living.

When I was fit to move I was strapped on to a mule, myself on one side

and two men on the other, and in that way I was carried down to the sea

and put on board ship, in which I came home to Portsmouth, and there,

before we landed, Queen Victoria steamed round and sent on board to

inquire about us.

For two years I had not slept in a bed, I had endured privations which I

cannot describe, I had witnessed horrors which I dare not speak about,

and now I seemed to be in paradise, for on board the ship I had port

wine and stout and every good thing that an invalid could need. These

comforts were some recompense for the privations we had gone through at

the seat of war. But the greatest joy of all was the reunion with my

husband.

There was not to be much peace or rest for us. Scarcely had we settled

to our home happiness before we were ordered to India, where the right

wing of my regiment took part in the Mutiny. But neither my husband nor

myself shared in that dreadful work. In India I was separated from him

again, and by myself I travelled down the country for several nights to

join a missionary’s wife, who was coming home, after spending many years

in the country, where, till she saw me, she had not set eyes on a white

women for nine years. The terror of the Mutiny had turned her hair quite

white.

My Army life was not all sorrow, and it was relieved by plenty of

humour. I remember that in India the drum major of my regiment died, and

a smart young man went to get his staff and tunic, having been promoted

to the post. He was a young fellow who had often sworn he would never

marry, yet, when he got the staff he said: “Well, I may as well take the

widow over, too!” And he did. He married her within a few days.

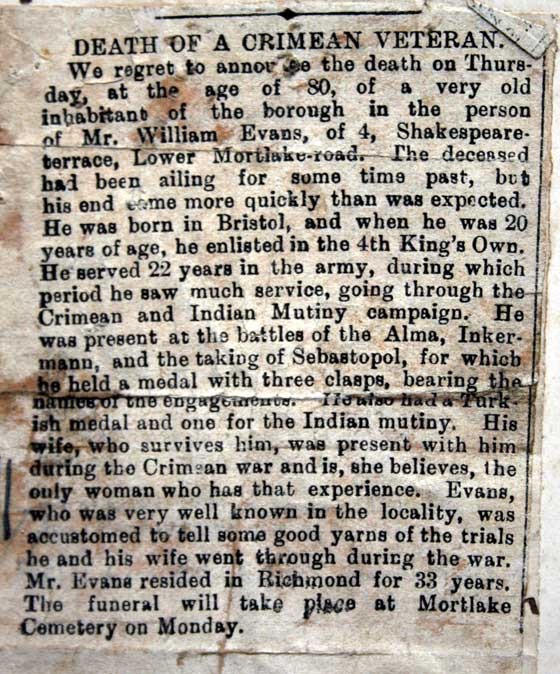

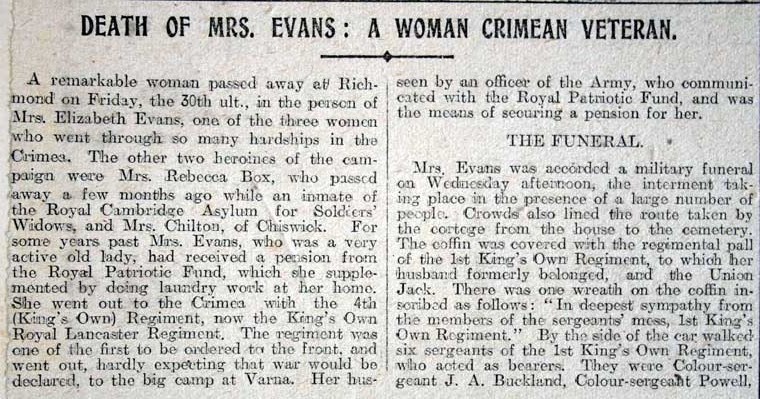

Deaths of Mr and Mrs Evans

Newspaper cutting, early 1900s.

The Lion and The Rose, 1914

From the Lion and The Rose, July 1914:

In our last issue will be found an account of Mrs Elizabeth Evans,

who went through the Crimean Campaign with the Regiment. One of

the last wishes was that her husbands medals should be given back to the

old Regiment. Accordingly Colonel Sparks JP who lived at Richmond,

and knew the old lady, arranged for the medals to be sent to this

Battalion. The Medals are the Crimean with clasps Sebastopol,

Inkerman, Alma; the Turkish Medal; and the Indian Mutiny Medal.

Mounted in a case and are hung on the wall of the ante-room in the

Officers Mess.

Sadly there is no trace today where these three medals are. The

museum has a Crimean Medal to a William Evans, which may well be the

medal mentioned above. The Turkish medal and Indian Mutiny medal

is not known, however there is no William Evans on the Indian Mutiny

Medal roll - only a Hugh Evans and a Joseph Evans. May be one day

we shall find the three medals for sure?

Only a proportion of our collections

are on display at anyone time. Certain items are on loan for display

in other institutions. An appointment is required to consult any of

our collections which are held in store.