The Great War Centenary

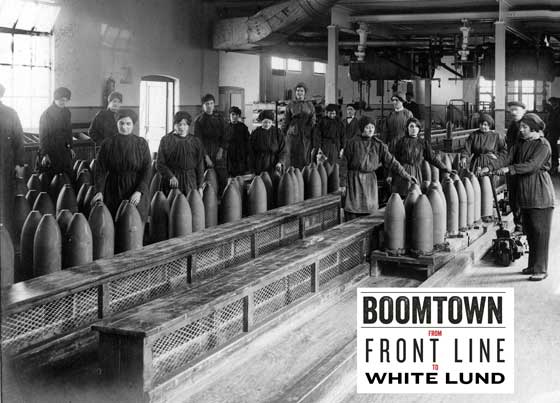

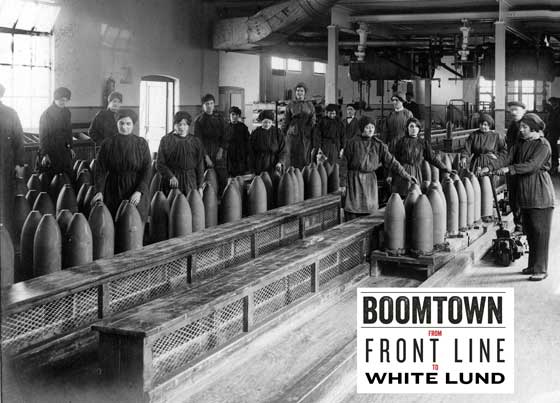

1917 - ExhibitionBoomtown - From

Front Line to White Lund

How Did People React?

Although the works were ‘officially’ a secret, local residents were

well aware of what was being produced at White Lund. When the explosions

started, around 10.30pm on 1st October, some people thought it was a

German Zeppelin airship bombing raid. Others, no doubt, guessed the real

source.

The Lancaster Observer’s report of the explosion was withheld by censors

until 24th January 1919:

‘A violent explosion, a crash, a rumbling echo around the neighbouring

fells, a shaking of everything on the surrounding earth, and

instinctively the great mass of humanity, whether asleep or awake, had

full knowledge.’

The Daily Post in Preston wrote its own report but was not able to

publish this until 25th January 1919. In this they stated that:

‘Thirty thousand people of Lancaster, Morecambe and surrounding villages

wandered through the night in all states of deshabilie, taking to the

hills or the open expanse of seashore, and there was not a country land,

church, chapel or barn for miles around where people were not seeking

shelter from what they deemed to be imminent danger.’

We cannot be sure of the numbers moving around in search of safety. We

do know that many made for Morecambe to shelter on the beach, protected

by the prom walls. Some munition workers, who were ‘on days’, were told

to get up and run to Heysham Harbour. Others made for the surrounding

countryside – Quernmore, Galgate, Hest Bank, Bolton-le-Sands, Hornby and

Caton.

There were many reports of windows blowing in with the many blasts. Some

windows remained broken for weeks afterwards.

In reports after the disaster the claim that Special (Police) Constables

were keeping folk away from their homes were investigated and denied by

the Police.

A handbill from the Borough of Morecambe shows that claims for reglazing

broken windows were to be dealt with by the Ministry of Munitions.

Perhaps a similar arrangement also existed in Lancaster.

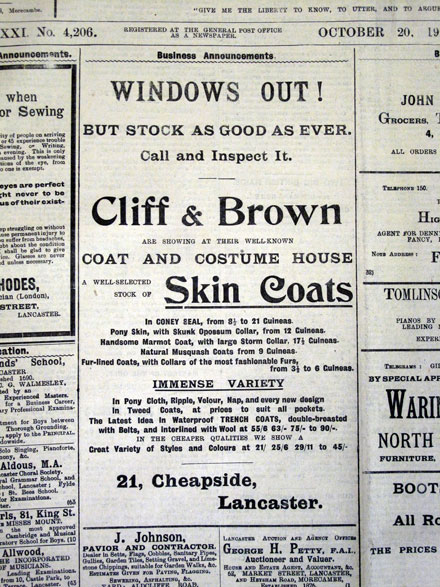

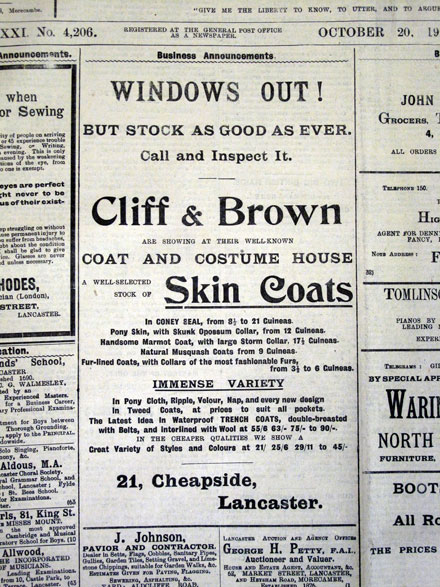

An advert for Cliff & Brown, Cheapside, Lancaster, is headed "Windows

Out!" clearly indicating that their windows had suffered damage and

still had not been replaced by 20th October 1917.

Although many munitions workers were paid two weeks’ wages and

encouraged to leave for home or for other works, some must have stayed

in the area. The local paper, on 28th October, said:

‘During the past week a good many girls have availed themselves of the

rooms at St. Lawrence’s Schools opened last week by the Lady Mayoress of

Morecambe. Willing workers have been most assiduous in doing what they

could to make the whole surroundings happy and bright. The atmosphere

created is such that it will prove attractive.’

St Mary’s National School (Lancaster) records in its log book

that ‘Plate glass windows [are] smashed to atoms’ but, miraculously, on

2nd October ‘Only slight damage in school, 4 broken windows, + 3 falls

of plaster. No school all day. Terrible explosion hourly expected, town

deserted. Explosions at intervals all day and night.’

Skerton Council School’s log books show more damage:

‘Owing to the great disaster which took place at the Munition Works on

Monday Oct 1st, the school was closed on Tuesday – only two children

presented themselves. The attendance during the week gradually improved

but did not reach the normal state. About 60 panes of glass and two

clocks were damaged by the concussion.’ In the Infants some 23 window

frames were broken along with the large window fixtures and springs.

Sightseers & souvenir hunters

‘The Lancaster Observer mentions sightseers ‘engaged in the task of

picking up souvenirs’ soon after site was secured. The museum has a

number of pieces of shrapnel found and saved by local people. There may

be much more still in the hands of local families.

Nervous disposition

Audrey Pearson, nee Fleetwood, says her mother, Ada Fleetwood, was

pregnant with Audrey’s elder sister Winne when the White Lund explosion

took place. Ada went down on to the beach during the explosions. Winne

turned out to have rather a nervous disposition and her mother always

said it was because of that experience.

Local stories have emerged in newspaper reports and in interviews

held in the Elizabeth Roberts Archive:-

‘I always remember when the White Lund explosion blew up. Mother was

working at the Projectile Factory on nights and he [Archie] was supposed

to be looking after us because he was the eldest. There were three loud

bangs come at our door in the bedroom and I shouted “Give up Archie

don’t act so daft.” I thought it was him playing the fool and it was the

first three explosions of White Lund and we landed at [walked to] Caton

Institute. Mother had to come looking for us the day after.’

Within a day or so of the explosion many workers had left Morecambe as

reported, with the above photograph, by the Daily Despatch on 4th October 1917.

© Images are copyright, Trustees of the King's Own Royal Regiment Museum.

You must seek permission prior to

publication of any of our images.

Only a proportion of our collections

are on display at anyone time. Certain items are on loan for display

in other institutions. An appointment is required to consult any of

our collections which are held in store.