The Great War Centenary

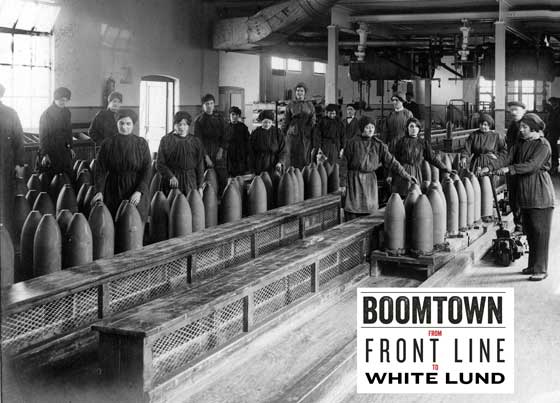

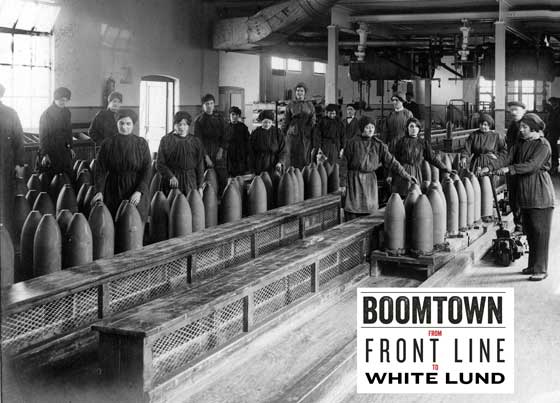

1917 - ExhibitionBoomtown - From

Front Line to White Lund

The Home Front

Regulation

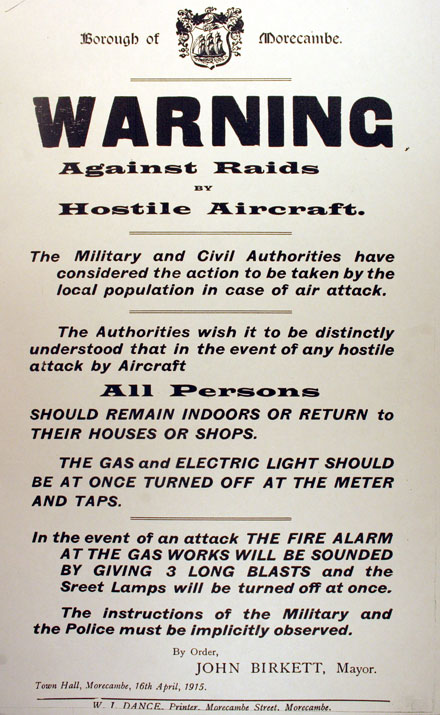

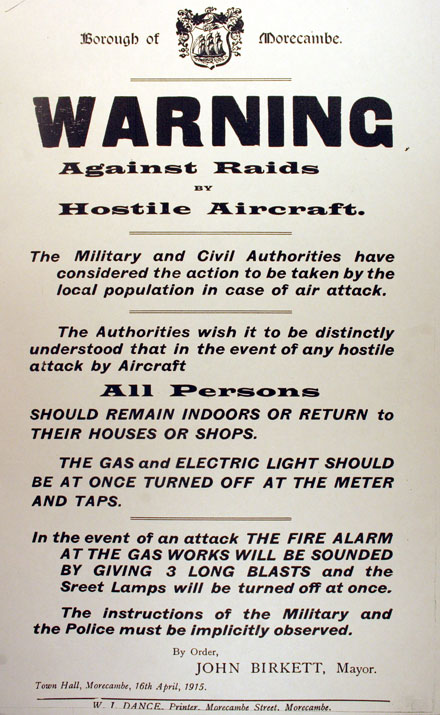

On 8th August 1914, within four days of the outbreak of war,

parliament passed the ‘Defence of the Realm Act’ (DORA). The country now

entered a time of complete regulation. You could be prosecuted for

spreading stories that caused alarm just as much as for anti-war

feelings. Censorship of the press led, unsurprisingly, to the virtual

news blackout on such disasters as White Lund Filling Factory’s fire and

explosions. People were no longer free to fly kites, start bonfires or

buy binoculars. Such was the fear of spies signalling to Zeppelins and

other subversive activity.

Borough of Morecambe warning of Air Raids, April 1915.

The National Registration Act meant men and women, between the ages of

15 and 65 years, had to register at their home location on 15th August

1915. Everyone had to submit their own application form and it seems

some 29 million forms were issued across England, Scotland and Wales.

They were processed locally and the information was compiled into a

central register for the Registrar General. It formed an up-to-date

record of people that could be targeted for recruitment into war work

etc. The scheme included identity cards that could be checked by the

police in cases of suspicious activity and, once conscription was

introduced in 1916, information for calling up men for the forces and

women to go to the Labour Exchange to be directed to war work.

As well as war work in local factories there were options of working in

new roles like ambulance driving, the new Women’s Land Army (1915

onwards) or even ‘on the buses’. There were some challenges for women in

this area interested in joining the Lancaster service, even though the

government had encouraged this from October 1915. It seems that women

bus conductresses in Lancaster were only permitted in 1918.

Supporting the war effort took many forms. The council allowed the City

Museum's building – the old Town Hall – to be used by the Local Branch of the

Volunteer Aid Detachment (VADs) for lectures on hospital work etc, the

Ladies Committee of a new club for soldiers’ wives as well as the

Military Authorities (who complained regularly about the state of the

heating).

Electric battery powered buses lined up in Market Square ready to take

workers to the works on Caton Road.

Hard times: food shortages

With large numbers of men no longer working the land, enemy

‘blockades’ and un-restricted submarine warfare disrupting food and

fertiliser imports and the need to feed serving soldiers, many people

were struggling. In October 1916 the local papers reported that bread

prices were at a record level. Bakers blamed the soaring cost of flour

caused by disruption of wheat imports. Advertising posters urged people

to ‘eat less bread’.

Those that had access to land could ‘grow their own’ but in this area

much of the housing has yards rather than gardens. We are used to

hearing about parks and common land being cultivated in the Second World

War but this was seen as a solution in the First World War too. In June

1917 the Council considered letters from the Food Production Department

about cultivating part of the land opposite the Projectile Factory on

Caton Road. It is not clear if this happened.

Those that had the time queued for what food was available in shops and

poster campaigns pressed the public not to hoard food and shop keepers

not to profiteer by raising prices for any stocks they held. Government

price controls on staple foods did not solve the problem and in 1918

rationing was introduced, first in London and then across the country.

Leisure, sports and the war effort

Despite long hours on war work sports and social activities thrived.

The Projectile Factory hockey and football teams regularly used Giant

Axe Field although they did fall behind with their rents from time to

time. In March 1918, though, their Ladies’ Football Club was grant free

use for one of their matches. Sports built links with the local

community and the Projectile Factory Ladies Hockey Team is known to have

played the fairly new Lancaster Girls Grammar School.

Fundraising events and activities were organised by churches, businesses

and charitable organisations. The council regularly granted free use of

the Ashton Hall in the (new) Town Hall in Dalton Square for concerts and

socials as long as the proceeds were donated to a specific cause. The

Projectile Factory Male Voice Choir concert in February 1917 pledged one

third of their proceeds to the King’s Own Prisoner of War Fund and in

January of the following year their Workers’ Hospital Committee pledged

all the proceeds of their concert to the ‘Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Free

Buffet’ on Preston station.

Some groups held practical, activity meetings using their skills at

hand. Knitting clubs for ‘comforts for soldiers’ were popular. As well

as sending parcels off to family members ‘at the front’, the King’s Own

Prisoner of War Care Committee sent much needed food and clothing

parcels to interned prisoners.

Edith Browning, one of the bus conductresses employed in Lancaster in

1918 due to the shortage of men.

Accession Number: LM2001.1

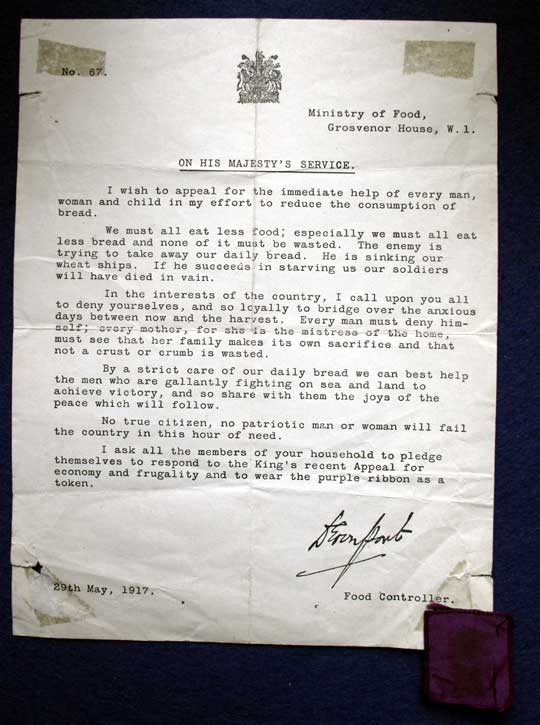

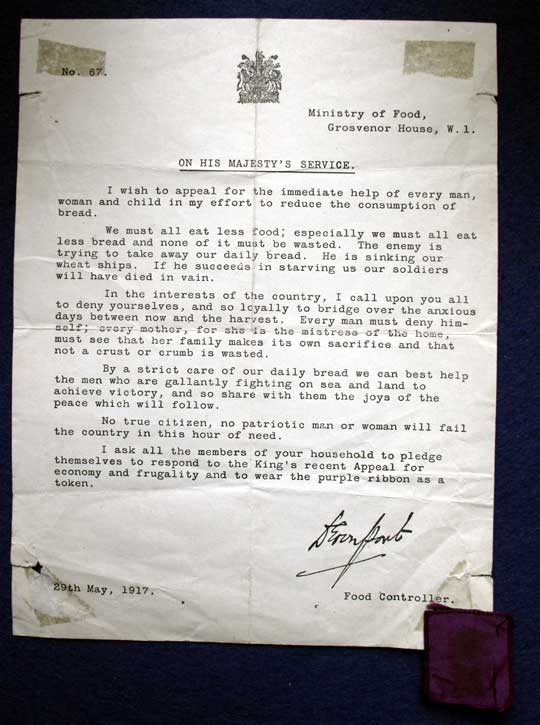

Letter from Viscount Devonport, Food Controller at

the Ministry of Food, 19th May 1917.

Circular from the Ministry of Food 29 May 1917. Re reduction of

consumption of bread.

Accession Number: KO0933/07

Ministry of Food

Grosvenor House W1

On His Majesty’s Service

I wish to appeal for the immediate help of every man, woman and child in

my effort to reduce the consumption of bread.

We must all eat less food; especially we must all eat less bread and

none of it must be wasted. The enemy is trying to take away our daily

bread. He is sinking out wheat ships. If he succeeds in starving us our

soldiers will have died in vain.

In the interests of the country, I call upon you all to deny yourselves,

and so loyally to bridge over the anxious days between now and the

harvest. Every man must deny himself; every mother, for she is the

mistress of the home, must see that her family makes its own sacrifice

and that not a crust or crumb is wasted.

By a strict care of our daily bread we can best help the men who are

gallantly fighting on sea and land to achieve victory, and so share with

them the joys of the peace which will follow.

No true citizen, no patriotic man or woman will fail the country in this

hour of need.

I ask all the members of your household to pledge themselves to respond

to the King’s a recent Appeal for economy and frugality and to wear the

purple ribbon as a token.

[Viscount] Devonport

Food Controller

29th May 1917

Accession Number: KO0933/07

Food queue at Speight’s Grocers, Brock Street, Lancaster

LM98.3

© Images are copyright, Trustees of the King's Own Royal Regiment Museum.

You must seek permission prior to

publication of any of our images.

Only a proportion of our collections

are on display at anyone time. Certain items are on loan for display

in other institutions. An appointment is required to consult any of

our collections which are held in store.