141 Days: The Battle of

the SommeNo Manís Land

In the book Songs and Slang of the British Soldier: 1914-1918,

published in 1931, ďNo Manís LandĒ is described as ďa strangely romantic

name for the area between the front line trenches of the British and

German armies, held by neither, but patrolled, at night, by both.Ē

No Manís Land was a terrible place; a piece of ground sometimes only a

few metres wide. The ground would be turned up and cratered by the

constant bombardment of shells from both sides. The shattered remains of

trees mixed with wooden and iron picquets (stakes) between which barbed

wire was strung. The smell of death was all around, combined with the

smell of gun powder and maybe even poison gas which had sunk to the

bottom of the craters.

Worse still, there could be the disturbed graves and cemeteries of

soldiers killed in previous battles, but unable to rest in peace as more

shells ripped the ground apart.

It was not a place to be, in daylight, but it was the only way to reach

the enemy. German soldiers had easily picked out the areas where the

British barbed wire had been cut in preparation for the attacks of the

Somme. They could easily train their Maxim machine guns on to these

positions and cut down advancing troops, with unbelievable ease and

devastation.

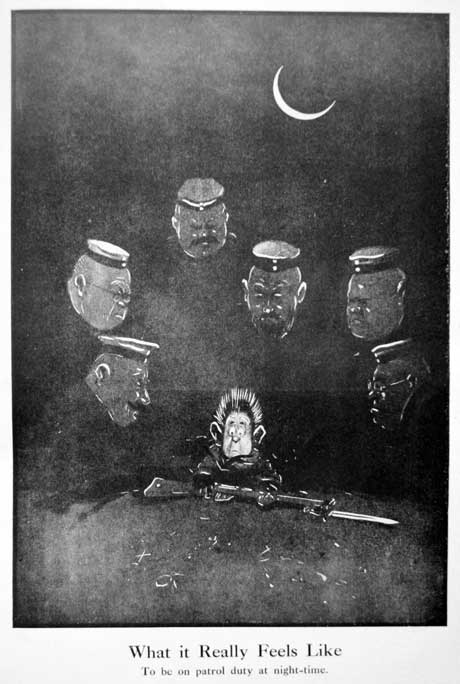

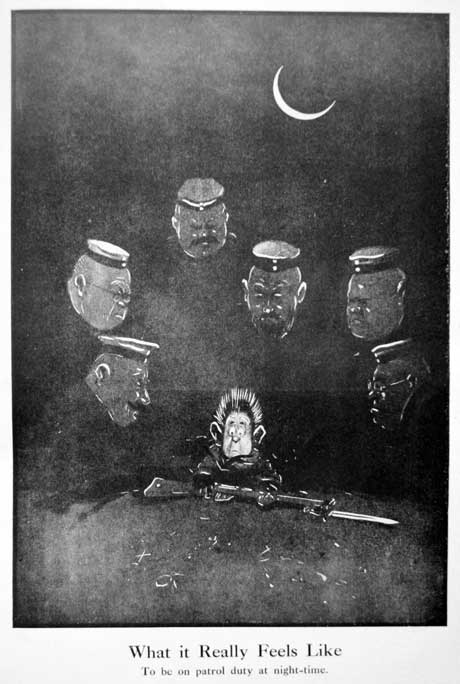

At night time No Manís Land was a different place. Both sides sent out

patrols, to listen for the enemy and obtain what ever intelligence they

could. They may even be a raiding party sent to capture enemy soldiers

who could be interrogated. On a dark night it was really dark, on a

night with a full moon it could be far too light! Both sides would fire

flares from Very pistols illuminating, the ghostly shapes of soldiers

patrolling or working for a few minutes.

Working parties operated almost on a nightly basis in No Manís Land.

Some of these men were killed and wounded by enemy fire. Barbed wire

defences had to be laid out, repaired and renewed, as shells could

easily destroy the effectiveness of the wire. Barbed wire also had to be

cut and removed, in preparation for an attack, to permit our soldiers

easy passage to the German lines. Special path-finder patrols would go

out at night and tape Ė or mark out Ė a route to be followed by the

attacking troops.

No Manís Land was the worst place a soldier could be. It was far worse

than a trench, which offered a good amount of protection from enemy

fire. No Manís Land was the killing zone, even on a quiet night, when

little was happening. A soldier could meet his end whilst carrying out

some mundane manual duty, with nothing more threatening than a pick or

shovel.

No Manís Land could be peaceful too. Soldiers like Private William

Hodgson, of the Kingís Own, could sit and listen to a sky lark singing

high above the ground, as if all was normal and the war was a thousand

miles away.

Next: Working Parties

Supported by the Sir John Fisher Foundation and the Army Museums

Ogilby Trust

© Images are copyright, Trustees of the King's Own Royal Regiment Museum.

You must seek permission prior to

publication of any of our images.

Only a proportion of our collections

are on display at anyone time. Certain items are on loan for display

in other institutions. An appointment is required to consult any of

our collections which are held in store.